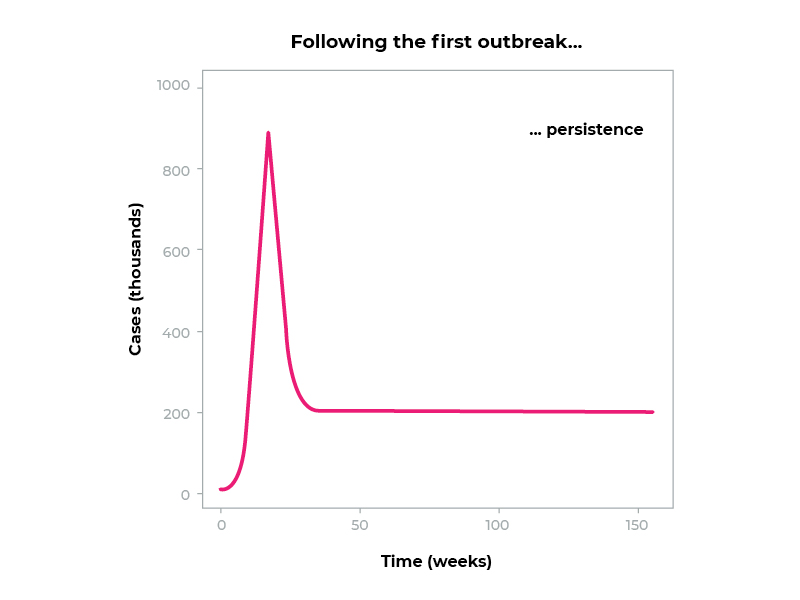

We may be anywhere on the first curve of this graph. The important part is, in the words of Dr. Rob Grenfell, “this virus is going to stay with us.”

This virus is going to stay with us.

It’s here.

It’s jumped from animals to humans, and we’ve got it. The first spike represents this current pandemic period, which will go on for around about one or two years, sadly, but the virus will continue to be a challenge and a problem to us for time immemorial from now.

Dr. Rob Grenfell

When planning for a future with a rapidly aging population, we need to consider infection control.

The Royal Commission agrees.

There is nothing more important to help providers prepare for and respond to COVID-19 outbreaks than access to high level infection prevention and control expertise.

Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety

If infection control is an ongoing concern, how do we think about it in the future? How do we shift from short-term tactics to long-term strategies? And how do we balance life-saving isolation with life-enhancing social interaction?

First, let’s establish why limiting interaction is so important.

It’s because of the way COVID-19 spreads.

Methods of Transmission

COVID-19 is usually spread by droplet and aerosol transmission during close contact:

Current evidence suggests that the virus spreads mainly between people who are in close contact with each other, typically within 1 metre (short-range). A person can be infected when aerosols or droplets containing the virus are inhaled or come directly into contact with the eyes, nose, or mouth.

The virus can also spread in poorly ventilated and/or crowded indoor settings, where people tend to spend longer periods of time. This is because aerosols remain suspended in the air or travel farther than 1 metre (long-range).

World Health Organisation

When an infected person ‘coughs, sneezes, talks or sings’, they expel ‘respiratory droplets’ of >5-10 microns (0.001 mm) in diameter. These droplets will ‘settle out of the air rapidly, within seconds to minutes.’ This means droplets will only infect those in direct physical or face-to-face contact.

Airborne transmission through aerosols (droplets <5μm in diameter) is less common but threatening. These tiny airborne particles spread widely, and ‘remain suspended in the air for minutes to hours.’

The WHO is still debating airborne transmission of COVID-19. Few reliable studies have found COVID-19 airborne transmission in normal clinical conditions. However, reports on some outbreaks have suggested it is possible.

Cutting down airborne transmission is harder than standing 1.5 metres apart. It requires correct airflow, ventilation, and even full isolation in some cases.

So, how are these methods of transmission a problem for aged care facilities?

The Problem: Aged Care Buildings

Across the healthcare sector, the layout of sites have shifted. Traditional office-like spaces with separate rooms have changed to open-plan, domestic living areas.

Our hospitals, particularly aged care facilities, have been built to allow people to interact with each other. These are perfect settings for the virus to spread in very vulnerable people.

Dr. Rob Grenfell

To illustrate this change, here’s an image of a traditional healthcare setting, compared with an example of a modern aged care facility.

These layouts are very different, even from an aerial view.

The Fairfield Infectious Diseases Hospital had separate buildings and defined boundaries.

The modern aged care facility has connected wings and common spaces. Little differentiates it from the surrounding suburbs.

In management, the buildings are even further apart.

Modern aged care facilities include common areas and hallways connecting buildings. Residents are encouraged to use these common areas and roam in the hallways. This increases the difficulty of controlling infections that are transmitted by close contact.

Let’s go over some solutions for infection control.

Solutions for Droplet Transmission

Medical quality masks and gloves are successful for preventing droplet transmission.

However, this is a short-term tactic. Continuous use of personal protective equipment is cost prohibitive. It also restricts communication and human connection in direct care.

Another tactic that was used frequently during 2020 was ‘symptom isolation’. This meant immediate isolation and COVID testing of residents that show symptoms, such as fever, coughing or sore throats.

The WHO supports this method as effective, as stated in their infection control brief.

It is clear from available evidence and experience, that limiting close contact between infected people and others is central to breaking chains of transmission of the virus causing COVID-19. The prevention of transmission is best achieved by identifying suspect cases as quickly as possible, testing, and isolating infectious cases.

World Health Organisation

But this is also for emergency use. Isolation decreases quality of life and can cause distress in cognitively impaired residents.

Advice from the WHO recommends a suite of other infection prevention and control measures:

Other infection prevention and control (IPC) measures include hand hygiene, physical distancing of at least 1 metre, avoidance of touching one’s face, respiratory etiquette, adequate ventilation in indoor settings, testing, contact tracing, quarantine and isolation.

World Health Organisation

Solutions for Airborne Transmission

There’s one key section of this suite that isn’t used. Health authorities haven’t addressed ventilation requirements in aged care when aerosols are a possibility.

This is especially concerning when we know that almost half of Victorian hospital isolation wards lacked appropriate ventilation systems in 2020.

Dr. Rob took a question on improving ventilation in aged care for COVID-19. He said:

You do need to have a very regular transfer of the air and fresh air coming through, and HEPA filters, of course, will in fact remove the virus. Coronavirus is a great big lolling virus. It’s not a small one, like some of the other ones we deal with, so it actually is readily taken out by HEPA filtration, but that’s expensive.

So, in the interim, the idea is in fact outside air is a good thing. So outside air is one way of looking at this, and ventilation I would say that we will ultimately move to high flow rates and HEPA filtration in so many communal buildings, but that’s an enormous cost.

Dr. Rob Grenfell

The WHO says:

A well-designed, maintained and operated system can reduce the risk of COVID-19 spread in indoor spaces by diluting the concentration of potentially infectious aerosols through ventilation with outside air and filtration and disinfection of recirculated air. Proper use of natural ventilation can provide the same benefits.

World Health Organisation

The WHO also provide an in-depth research paper to guide ventilation improvements, where necessary.

Dr. Rob said, ‘there is a theoretical risk that air handling systems without filters could lead to viruses being transmitted between rooms’. Scientists haven’t conducted enough research on airborne COVID-19 to be sure.

Biodiversity scientist Jessica Green researched the bacterial similarities of rooms linked by the same air conditioning system.

She focused on how air systems and people disperse microbes. The research could prevent hospital-acquired infections through intentionally designed microbial biomes.

What Can You Do?

Dr. Rob provided some practical advice:

- Check and adhere to the Australian standards for ventilation.

- If your system allows it and can maintain indoor temperatures, use a lot of outside air to dilute any airborne viruses.

- Maintain air handling systems and increase internal surface cleans.

- Keep your focus on employees staying home if they are sick, physical distancing and hygiene.

The next step? Check your ventilation and airflow against the WHO guidelines here. Enlist a heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) system expert to help.

Potential improvements to your system could include:

- Directing air change rates,

- Installing high efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filters, or

- Using increased natural air flows from outside.

The system should be ‘maintained regularly by suitably qualified staff according to an agreed maintenance plan, and accurately documented in a maintenance record.’

A smart choice is the i-air by our partner i-team ANZ – a new technology air purification device for medium-to-large spaces.

Conclusion

To protect your vulnerable residents, you need to guard against all COVID-19 transmission. Preventing airborne as well as contact transmission is critical for your facility.

If you don’t control COVID-19, there’s a risk to your residents’ lives. Since the virus is going to stay with us, we must prepare for the radical systemic change that’s coming.

Talk to our hygiene experts about how we can help to improve your infection control.

* References

- Grenfell, Dr. R. 2021. Insights from CSIRO: the Outlook for Aged Care in 2021 [Webinar]. [Online]. Veridia, 17 November 2021.

- Briggs, L., Tracey, R. (2020) Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety Aged care and COVID-19: a special report, Australian Government, 2019. Page 22. Found at: https://agedcare.royalcommission.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-10/aged-care-and-covid-19-a-special-report.pdf

- Grenfell, Dr. R. 2021. Insights from CSIRO: the Outlook for Aged Care in 2021 [Webinar]. [Online]. Veridia, 17 November 2021.

- World Health Organisation. 2021. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): How is it transmitted?. [ONLINE] Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/q-a-detail/coronavirus-disease-covid-19-how-is-it-transmitted. [Accessed 12 July 2021].

- World Health Organisation. 2020. Transmission of SARS-CoV-2: implications for infection prevention precautions. [ONLINE] Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/modes-of-transmission-of-virus-causing-covid-19-implications-for-ipc-precaution-recommendations. [Accessed 12 July 2021].

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. 2021. Scientific Brief: SARS-CoV-2 Transmission. [ONLINE] Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/science/science-briefs/sars-cov-2-transmission.html. [Accessed 12 July 2021].

- World Health Organisation. 2020. Transmission of SARS-CoV-2: implications for infection prevention precautions. [ONLINE] Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/modes-of-transmission-of-virus-causing-covid-19-implications-for-ipc-precaution-recommendations. [Accessed 12 July 2021].

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. 2021. Scientific Brief: SARS-CoV-2 Transmission. [ONLINE] Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/science/science-briefs/sars-cov-2-transmission.html. [Accessed 12 July 2021].

- World Health Organisation. 2020. Transmission of SARS-CoV-2: implications for infection prevention precautions. [ONLINE] Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/modes-of-transmission-of-virus-causing-covid-19-implications-for-ipc-precaution-recommendations. [Accessed 12 July 2021].

- World Health Organisation. 2020. Advice on the use of masks in the community, during home care and in healthcare settings in the context of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak. [ONLINE] Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/advice-on-the-use-of-masks-in-the-community-during-home-care-and-in-healthcare-settings-in-the-context-of-the-novel-coronavirus-(2019-ncov)-outbreak. [Accessed 11 July 2021].

- Grenfell, Dr. R. 2021. Insights from CSIRO: the Outlook for Aged Care in 2021 [Webinar]. [Online]. Veridia, 17 November 2021.

- World Health Organisation. 2021. Roadmap to improve and ensure good indoor ventilation in the context of COVID-19 . [ONLINE] Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240021280. [Accessed 11 July 2021].